This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

Marxism and Philosophy in the 21st Century

C Ritchie, Manifesto Press, £10

LAUNCHED by a revitalised Manifesto Press as part of its Workers and Students’ Guides, C Ritiche’s Marxism and Philosophy in the 21st Century is an unusual contribution to the history of philosophy.

This is no endless tome filled with esoteric ruminations or thought experiments testing one’s moral mettle — it goes straight to the point.

Ockham’s razor has now become Ritchie’s “cut the crap.” This can easily be read in one sitting, and for anyone who has ever studied philosophy before, this is a drive-by shoot-out with Western philosophy, unashamedly from the perspective of creating change and filled with reflections on the actual meaning of philosophical conclusions for a life spent in work and study.

Marx himself had a deep interest in philosophy and he rapidly become disillusioned with the stale and inactive philosophical scene in academic Germany, and its reliance on religion.

Marx’s PhD thesis sought to show how religion had to yield to philosophy, a precursor to the well-known conclusion that “the philosophers have only interpreted the world in various ways: the point, however, is to change it.”

Philosophy, despite its reputation as something only for academics, hippies and mystics, is an important subject and no less in Marxism as it attempts to answer the fundamental questions: what is there, how do we know and what do we do about it?

It’s sometimes said that four-year-olds repeatedly asking “why” to every answer provided by an adult make the best philosophers. Every adult who’s ever had to answer such a four-year-old knows it often concludes with “just because,” or “its just the way things are,” when in fact the actual answer involves understanding meaning, value and power relationships.

In Marxism, philosophy provides a theory of meaning that underpins much of the later conclusions. But Marx is nothing if not practical and any theory of meaning which affirms a worker’s needs are best met when he’s dead in heaven (having been a good guy on earth) is basically a scam.

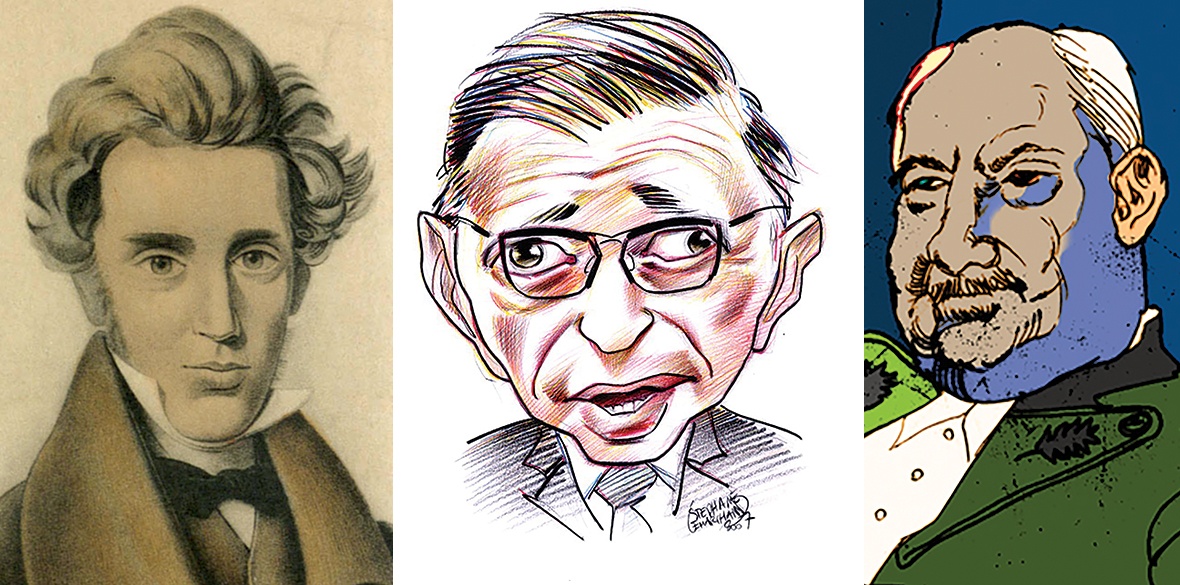

Ritchie’s tour of Western philosophy covers all the basics from the Greeks (which is where Marx himself started) through Cartesianism (which is skilfully put aside without resorting to Wittgenstein’s private language argument), into the empiricists and then the Germans, of course through the figure of Hegel, who was highly influential on Marx and Marxism.

The thoughts of Kierkegaard, Heidegger and Sartre are correctly identified as essentially trying to explain why we’re blaming ourselves for being depressed, without reference to the external world, while Nietzsche says we need to overcome it all by the use of will alone.

Each section is interspersed with real-life examples of frustration in a working life, or dealing with the enquiries and answers of a nine-year-old daughter, much of which reflects Ritchie’s varied career as an academic, chef, musician and dad.

Gramsci is contextualised in his historical background as a participant in labour struggles followed by his long time in prison, and his significant contributions to Marxism through his theories of cultural hegemony.

Ritchie notes at the beginning of this work, nowadays “meaning” is now often delivered not from the pulpit or the professor’s chair or even the workplace, but from large capital interests and privately owned media houses and their in-house “experts.”

An essential tool in undoing the inversion of facts often presented from these experts is understanding meaning, and Ritchie provides a good practical basis in understanding the key philosophical ideas and figures in Western philosophy and evaluating them for practical use.

The book ends with a discussion on freedom and what is means to be free, a much abused word which can mean the freedom of the ruling class to command as much as it means liberation from constraint by the ruling class.

As Stalin said, real liberty can only exist where exploitation has been abolished; Ritchie ends by suggesting that Marxist philosophy itself might come to an end once its goals have been reached.

This is a concise overview of Western philosophy and is written without academic terminology or pretension. Manifesto Press is aiming its series at working and younger readers with an interest in changing the world, and this work clearly engages that audience without either distorting philosophy or alienating the readers.

There are plenty of pointers for onward study, but to push the academic-turned-chef metaphor probably a step too far, this is a very solid first course.