This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

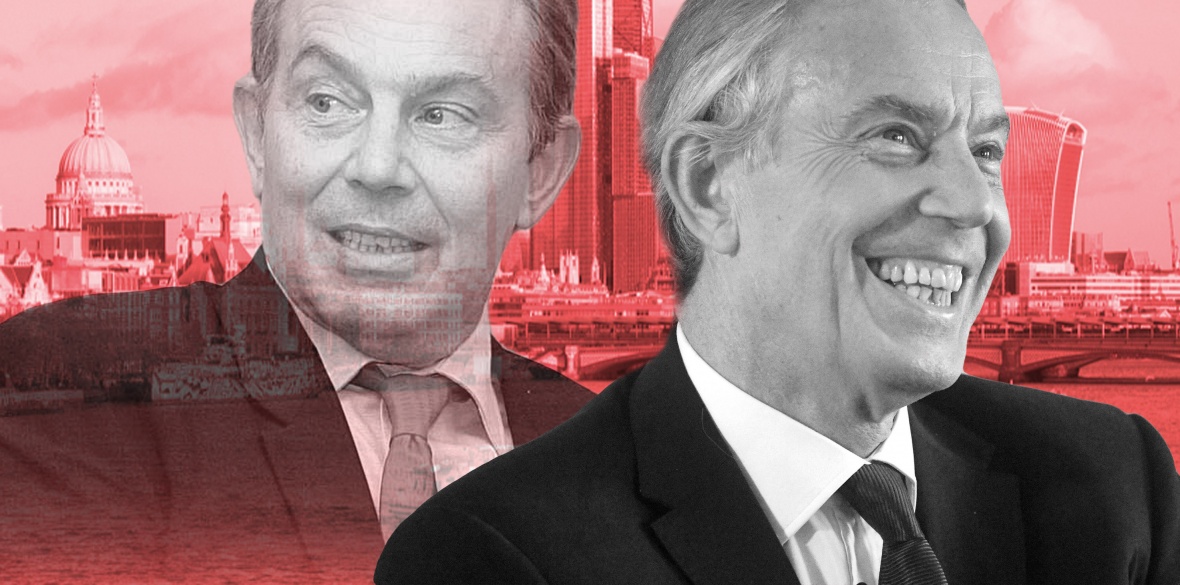

NEWLY released papers from the New Labour government elected in 1997 show how Blair sold out the unions on the key issue of recognition, overruling his own ministers to side with the CBI in a move that stopped a key reform dead.

Labour’s 1997 manifesto said “the key elements of the trade union legislation of the 1980s will stay — on ballots, picketing and industrial action,” so Thatcher’s anti-union laws would stay — but he also promised that “people should be free to join or not to join a union. Where they do decide to join and where a majority of the relevant workforce vote in a ballot for the union to represent them, the union should be recognised.”

New Labour offered the unions a compromise: continued restrictions on strikes, but a big prize in legally enforceable union recognition, which would have been a game changer.

But when the new Fairness at Work proposals emerged in 1998, the Labour government said unions had to do more than win a majority in a ballot. They had to win at least 40 per cent of the entire workforce, whether they voted or not.

This killed the proposal stone dead. No political party could become a government if it had to win 40 per cent of the entire electorate rather than a majority of actual voters. Blair himself won his 1997 “landslide election” with a result of 43 per cent, but even with the high voter turnout of 71 per cent, this only translates to 31 per cent of the entire electorate.

Everybody — employers, the press, Labour members and unions — thought the manifesto promise meant winning a ballot, not the unachievable 40 per cent of the entire workforce.

The National Archives released Cabinet Office files covering the first years of Blair’s government on New Year’s Eve 2021. The “meetings with unions” file details the sellout.

On March 27 1998 a Number 10 adviser wrote a note to Blair recording a meeting between the “minister without portfolio” Peter Mandelson and TUC president John Edmonds which he “sat in on.”

The note tells Blair, “Much of the conversation was taken up by John’s recital of how there had been collusion between people around you and the CBI to undermine the manifesto commitment on union recognition. He claimed the unions had been completely unaware that the words in the manifesto could mean anything other than how they are now interpreted by the TUC.”

There is plenty of evidence of Blair colluding with the CBI in the files. They also show he overruled his own ministers to push through the CBI’s anti-union plan. In particular he overruled Margaret Beckett, the Cabinet minister supposedly in charge of employment rules.

An April 16 1998 letter from Blair’s home affairs secretary Andrew Lapsley says, “The prime minister called the president this afternoon to talk about union recognition” — meaning Beckett, who was president of the board of trade — the old-fashioned name for business secretary.

Beckett was the Cabinet minister in charge of union recognition. According to the letter, “The president [Beckett] said that she had two reservations about 40 per cent. First, it was objectively just too high to be practical. Secondly, it was the same level which at which the threshold had been set for the unsuccessful referendum on Scottish devolution in 1979. This sent a very discouraging signal.”

Beckett wrote a paper recommending a lower threshold but, “the prime minister said that he had looked at the paper,” and, “having considered it further did not believe that the government should move from a position of 40 per cent of the workforce of a company supporting recognition in a ballot.”

Beckett tried to persuade the prime minister: “Union recognition remained the touchstone issue,” she wrote, arguing that inevitably “initially employers were not going to like it” but they would get used to it. Blair was firm, saying he “felt that 40 per cent was still as far as the CBI could go now, or that he could present to the public and the media.”

A May 12 1998 note says another minister tried persuading Blair: Scottish secretary Donald Dewar phoned Blair on “union recognition” to “warn him” on problems with the 40 per cent threshold. Dewar said he “would rather not be in the position of defending 40 per cent” and “feelings were running high on the backbenches on this issue.”

Dewar backed Beckett’s point, saying, “Suggestions the government had plumped for a 40 per cent threshold for union recognition were causing a major stir in Scotland with both the unions and the SNP strongly opposed. The 40 per cent figure had difficult connotations in Scotland because it was on this hurdle that the 1979 devolution referendum had failed” — in Scotland the feeling that 40 per cent of the total electorate was a cheat was well established. According to the note, “The prime minister reacted robustly,” saying, “it was crucial that the government did not alienate business support.”

The files show that, as the TUC claimed, Blair was colluding with the CBI. For example a Note for the Record marked “restricted — personal” records how “the prime minister spoke to Adair Turner [head of CBI] on the telephone last night” about “trade union recognition” written by then policy secretary Jeremy Heywood.

Heywood says, “the prime minister said that he wanted to tell Adair — completely off the record — where the government now was,” telling Turner “40 per cent of the workforce” was the “required ballot majority.” Blair added, “he knew the trade unions would be disappointed by the outcomes,” but that it was “important that the CBI was supportive.”

The New Labour government did bring in new workers’ rights reforms — including the minimum wage — but they tended to be individual rights. Union recognition would have been a collective right and a game-changer, a real shift in power. Increased union membership would have also created a more solid voting base for future Labour governments, instead of the stagnating union membership and the alienation of working class votes for Labour we saw in the 2000s.

In the 1930s Roosevelt’s New Deal government in the US introduced the kind of majority-vote union-recognition rules that Blair promised then undermined. It genuinely changed US society and created a new grassroots force for progressive reform across the board. Blair rejected this for an ultimately short-lived and shallow friendship with the CBI.