This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

JOHN HAYLETT was born on June 8 1945, on the eve of a general election that would sweep away wartime prime minister Winston Churchill in a landslide victory for Labour.

Liverpool, his home city, was as united in this turn to the left politically as it was divided over religion and football.

Born in a pub and brought up in a pre-fab, John was an Everton supporter while younger brother Steve followed Liverpool.

Their mother Marie, a shopworker, and sister June helped keep the peace when father Doug was away at sea.

As the brightest boy in the class, John passed the 11-plus exam to go to the Liverpool Institute, a prestigious grammar school.

His contemporaries there included Paul McCartney, future newsreader John Sissons and Stephen Norris — later to become a Tory MP best known for his nocturnal exertions of the mostly horizontal kind.

John was on chatting terms with Paul and his mate John before they went on to form the Beatles.

Football became one of young Haylett’s abiding passions. He also tried his hands at boxing, but found it difficult to accept that the hostilities should end inside the ring, not outside the gym afterwards.

Quite a few of the older, posher chaps at “The Inny” looked down on their rough and ready fellow pupils with the heavy Scouse accents.

Unapologetic about his egalitarian views, John’s early experiences of the class struggle often brought him home black and blue from the schoolyard.

But in the classroom, he learnt French and Russian. He also joined the Young Communist League and in 1963 the Communist Party.

In what was still the era of the cold war between the Soviet Union and US imperialism, he also enrolled in the Territorial Army. His motivation might have differed from that of his senior officers.

John’s head teacher bridled at the prospect of sending this articulate, pugnacious young rebel to university, refusing to write him a reference until he stayed at school a little longer and moderated his attitude.

John drew upon his fluency in Anglo-Saxon English to tell the headmaster what he could do with his reference. Then it was out of the school gates with him and into the wider world.

He briefly took a job in a bank and spent much of his money on politicking and — more like normal young men in that city at that time — bevvying to the Merseybeat music and the gritty, witty rhythms of the Mersey Sound poets.

This was the Liverpool of ex- and now anti-communist Bessie Braddock — who showed a “No Vacancies” notice to left-wing applicants for Labour Party membership, but also of ex-International Brigader and dockers’ champion Jack Jones and communist building workers’ leader Bill Jones.

At the age of 19, John left Liverpool never to live there again, although his love for that proletarian city and its people never left him.

For the next year or so, Monsieur Haylett travelled around France — not for the last time — before arriving in “that London.”

He worked as a grave-digger and then a croupier, quickly discovering that young women in the “swinging sixties” found his Scouse accent somewhat alluring.

It was there he met his first wife, Anne, with whom he had his much-loved daughter Marianne. The marriage broke down as the couple grew apart.

Later, he married Cherry, whose beloved son Leroy joined them from Jamaica. A whole world of West Indian music, food, cricket and card games in the pub opened up in John’s wide new circle of relatives and friends.

His deep and militant opposition to racism sprang from a personal passion as well as political principle.

By this time, he had dug himself into the world’s first International Telephone Exchange in Faraday House in the City, where his Russian came in handy.

He quickly gained a reputation as a dedicated, well-organised and fearless fighter for his fellow members of the Union of Post Office Workers.

As secretary of the telecoms branch, local strike leader and a delegate to union conferences, he came across the rather more headstrong Bernie Grant, later the Labour MP for Tottenham. They remained friends despite some political differences.

In this period, too, John’s commitment to the Anti-Apartheid Movement almost took a dramatic turn. He had come to know Ronnie Kasrils, who was recruiting young communists and socialists in Britain for clandestine work in South Africa for the African National Congress.

John duly acquired a false passport in the name of “John Lloyd,” although the word never came from Ronnie or the ANC to use it. After the fall of apartheid, Kasrils subsequently became South Africa’s defence minister.

After a stint at the ITE, John fulfilled his ambition to attend university and study Russian, French and economics.

Newcastle obliged without a reference from his old head teacher. While there, he threw himself into the party locally and was elected to its Northern district committee. With Cherry choosing to remain in London, his second marriage suffered.

Returning to London, John began what became a lifelong commitment to solidarity with the revolutionary people of Grenada, working closely with Jacqui Mackenzie and other New Jewel Movement representatives in Britain and with one of his favourite people, the legendary Ivan Beavis.

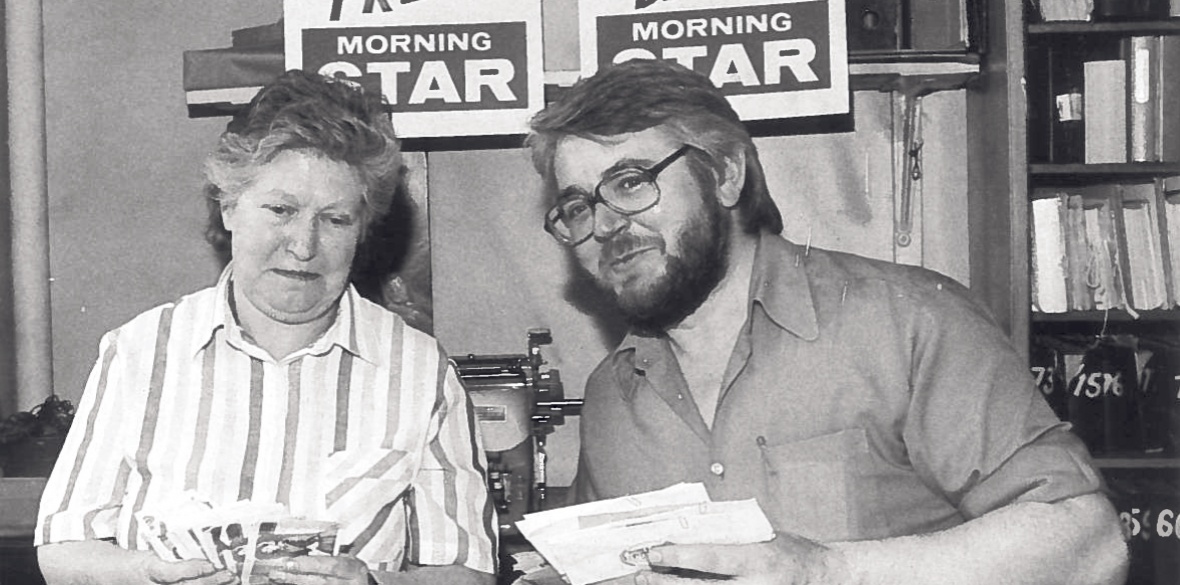

In 1983, after a stint painting and decorating for Hackney Council, Haylett the newshound was born. He joined the staff of the Morning Star, capable of writing and telling a story, but without any training in the noble and ignoble arts of the trade.

His appointment was controversial. Pressed by the so-called “Eurocommunist” trend, the revisionist leadership of the Communist Party under Gordon McLennan wanted to liquidate the class-based and pro-Soviet politics of the “daily paper for peace and socialism.”

Now it was rumoured in the newsroom that editor Tony Chater was hitting back by — in the words of then news editor Roger Bagley — “putting this hard-man in.”

Bagley Snr remembers the cub reporter as a fast and enthusiastic learner.

“We got a lot of graduates who felt they would ‘do two years at the paper’ as a sort of contribution to the movement, but weren’t really interested in learning journalism. But John picked up on everything,” Roger recalled later.

“One day I said to him: ‘You never know when a story might drop — it pays to have an overnight bag ready in case you need to dash off somewhere.’ The very next day he came in with a bag with essentials. He was ready to be sent anywhere at any notice.”

That immediately meant a trek alongside the People’s March for Jobs from Glasgow to London.

His next big assignment was covering the 1984-85 miners’ strike, not from an office in London but from the picket lines and pit villages of the coalfields.

John went on to other, higher posts in the Morning Star — although his pay stayed the same. True to his roots, he and his close colleagues had little time for the pretentious, gossipy cliques of media intellectuals.

“We drank with the production workers,” he once remarked.

In the Communist Party, his political judgement and tireless activism earned him an elected seat on the London district committee.

Fearful that its position would be weakened at the forthcoming London district congress in November 1984, the party leadership suspended and — in John Haylett’s case — expelled some leading London members and demanded that no new district committee be elected.

On November 24, McLennan in person called upon everyone present at the congress to follow him out of the hall. Most of the 250 delegates stayed put.

The most prominent dissidents — the “London 22” — were quickly suspended from party membership. In January, the executive committee expelled Tony Chater, deputy editor David Whitfield, London district congress chair Mike Hicks and leading trade unionists Ivan Beavis and Tom Durkin.

Others of the 22 were further suspended or expelled, including John’s close comrade Mary Davis.

Soon afterwards, John gravitated towards the Communist Campaign Group set up by Chater, Hicks, victimised British Leyland convener Derek Robinson and the secretary of the PPPS co-operative which owns the Morning Star, Mary

Rosser.

But the main focus of his work remained the Morning Star. On the foreign desk, he cultivated his connections with leading South African communists such as Jeremy Cronin and future president Thabo Mbeki.

After the CCG helped re-establish the Communist Party of Britain in 1988, he used his extensive knowledge and network to good effect as its international secretary.

Bridges had to be repaired with communist parties and national liberation movements around the world, many of which were in retreat and disarray after the collapse and counter-revolution in the Soviet Union and eastern Europe from 1991.

John helped ensure the re-established party’s swift recognition by parties and movements in the US, North Korea, Ireland, South Africa, India and Russia.

At home, the rise of the neofascist British National Party and in violent racist attacks on our streets prompted the birth of the Anti-Racist Alliance.

Its distinguishing features were a predominantly black leadership and a capacity to mobilise Britain’s black and minority ethnic communities.

But leading lights such as Marc Wadsworth also welcomed John Haylett onto its national committee as one of its most trusted members.

As the efficient and respected deputy editor of the Morning Star, it was widely assumed that John would be appointed to the top job in 1994 when Tony Chater announced his wish to retire.

Mary Rosser and husband Mike Hicks preferred her news editor and son-in-law, which explained an insidious whispering campaign that had begun some time previously.

A decision was postponed. Everything was then done to prevent the Communist Party’s political and executive committees from making a recommendation — including the falsification of minutes and a claim that one entire meeting had been a figment in the imagination of Haylett’s supporters!

Nevertheless, by the narrowest majority, the PPPS management committee appointed John Haylett the paper’s editor the following year.

In 1997, John travelled with CPB general secretary Mike Hicks, Mary Rosser and chair Richard Maybin in a delegation to China.

His series of articles in the Morning Star broke through many of the myths and distortions peddled from the right and the far-left about that country’s phenomenal development.

The visit also confirmed John’s view that his party desperately needed a change of leadership.

Supported by Richard Maybin, he nominated me and rallied the discontented to win a 17-13 majority at the January 1998 executive committee.

Retribution was swift. Within weeks, Haylett was suspended by Mary Rosser for “gross industrial misconduct.”

For possibly the first and only time in the history of the national press in Britain, most of the staff went on strike to demand the reinstatement of their editor.

Local MP Jeremy Corbyn was one of many to turn up on the NUJ picket line in Ardleigh Rd, complete with bicycle.

The journos decamped to nearby premises to produce editions of the “Workers’ Morning Star.”

Settlement terms agreed between Rosser’s supporters in the Socialist Action faction and me — known only to John Haylett — were rejected out of hand by the PPPS secretary.

With support draining away as the strikers stood solid for six weeks, the dispute went to mediation which found in favour of John Haylett on every count.

Back in post, John embarked upon an ambitious strategy to rescue the paper from financial collapse, soon backed by a new PPPS secretary Jenny Williams (followed by Richard Maybin), a newly elected management committee and the existing CPB executive.

Henceforth the paper would seek to grow rather than cut its way out of permanent crisis.

John continued with his political work, particularly in the anti-war movement. He worked closely with Halifax MP Alice Mahon in the Committee Against War in the Gulf and campaigned against the US invasion of Afghanistan.

In November 2001, as he was addressing a 500-strong meeting in Oxford town hall, ex-US president Bill Clinton’s daughter Chelsea made a noisy entrance with her security service bodyguards.

Backed by a barracking chorus of aggressive Americans, she interrupted the Morning Star editor as he was condemning the lack of media coverage of the thousands of civilian casualties in Afghanistan.

“You should remember the victims of the 9/11 terrorist attacks in New York,” she shouted out.

“That’s why we hold meetings like this, so that alternative viewpoints can be heard,” John replied, his paper having promptly and prominently condemned the mass murder of several thousand office workers on that day.

Chelsea Clinton reportedly bought a copy of the Morning Star shortly afterwards, on her way out of the meeting.

John’s go-for-growth approach culminated in a complete relaunch of the paper in June 2009 as a 16-pager with extra colour and also online, overseen by John’s loyal deputy and subsequent successor, the late Bill Benfield.

John moved into the new post of political editor, which better suited his new life in Cardiff.

In the early 1990s, he had met Sian Cartwright and her sister Rhian at the Wales TUC conference in Llandudno.

She had then moved to London to be with him, eventually securing a high-level position in the train drivers’ union Aslef, responsible for political education and industrial relations.

The union’s dynamic left-wing general secretary Mick Rix, together with RMT general secretary Bob Crow, were opening up vital new areas of practical and political support for the Morning Star in the labour movement.

Tony Benn and John Pilger wrote regular columns.

After Sian was appointed head of education with the Wales TUC in Cardiff, she moved back to the city and John happily went with her.

They were comrades in arms, sharing a passion for good food, wine, European travel and political argument.

He learned to love rugby, while she never learned to stop hating football.

As the love of his life, Sian brought John a new family of children and grandchildren to cherish alongside his other much-loved tribes and two recent great-grandchildren.

Their wedding in a country manor near Cardigan in 2003, at which I was honoured to be the best man, brought colour to that locality in every way possible.

Never had the good people of that Welsh-speaking town seen so many Caribbean faces all at once — and never had those wedding guests experienced such a warm welcome anywhere else in Britain.

John spent his last years helping to build the Communist Party, as a member of its Welsh committee, and winning new friends for the Morning Star.

He interviewed political leaders including Plaid Cymru’s Leanne Wood and Welsh First Minister Mark Drakeford. He made the Star the partner paper of the annual Merthyr Rising festival.

He remained as alert, incisive and knowledgable as ever. Morning Star editor Ben Chacko could always count on John for wise advice and the occasional barbed or congratulatory email.

Warm, witty and always ready to reconsider his views in the face of evidence and reasoned argument, the end came quickly after a superficially mild stroke.

On September 28 2019, he died in Sian’s arms, holding Marianne’s hand — a giant of the labour and communist movement at rest after a lifetime of struggle, tribulations and the many joys of love and comradeship.