This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

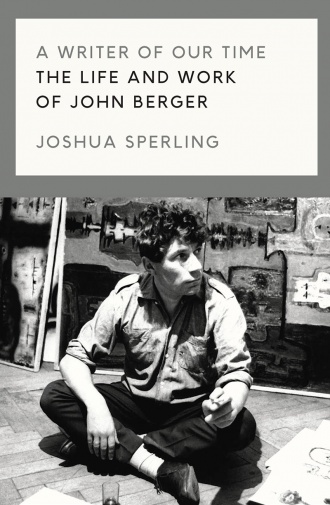

A Writer of Our Time

by Joshua Sperling

(Verso, £20)

WHEN John Berger passed away in January last year, all of his obituaries invariably started with a litany of vocations that could be ascribed to him — art critic, essayist, novelist, presenter, poet and still more. In this erudite and engaging biography, Joshua Sperling appraises that extraordinarily eclectic oeuvre in its entirety.

Rather than tracing his career chronologically, the book is structured around the concerns and questions that animated Berger throughout his life, such as the relation of art to revolution and society and the trials of being a committed artist.

Not only does this allow Sperling to show how these concerns overlap in his criticism, fiction writing and other artistic collaborations, it opens them so that they resonate with the present.

From these themed chapters, a braided narrative emerges. All there are his beginnings as Marxist scourge of the 1950s British cultural establishment, his controversial winning of the Booker Prize and his time as a provocative TV presenter before settling for the last four decades of his life in the peasant community of Quincy in rural France.

The development of his thought parallels the intellectual developments of the British left, influenced by the thawing of cold war binarism which led to the formation of the “New Left” and the revolts of 1968 and their aftermath. Occasionally, Sperling’s cleaving of Berger’s work to this historical arc can seem forced but more often than not Berger’s prescience is undeniable.

Refusing the dogma of much Marxist art criticism of his day, which would see art reduced to an instrument of propaganda, Berger was one of the first to see that revolution is as much about the form as it is about the content of an artwork.

“If an artist is painting a chair, he does not automatically make it a socialist painting by placing a copy of the Daily Worker upon it,” Berger once remarked. Cavalierly dismissing the paper’s authority to anoint revolutionary artwork, he instead prefigures the work of later Marxist critics like Fredric Jameson by detailing the revolution of perception inaugurated by modernist art.

While Sperling ably shows how Berger’s theoretical insights were often ahead of their time, his study never becomes an uncritical hagiography and, in particular, he flags up the particularly dated gender politics permeating much of his work.

Sperling’s book is a welcome intervention that does justice to the legacy of Berger’s thought and work which has been criminally underappreciated in Britain. His legacy is more than a provocative Booker Prize speech and a perennial set text of art history syllabuses.

During his life John Berger tirelessly illuminated the numinous and democratic possibilities of art to make us see the world anew and laying down the challenge for us to make it better.