This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

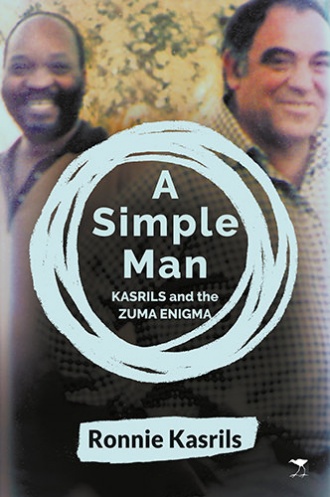

A Simple Man

by Ronnie Kasrils

(Jacana, £16.95)

THIS book's title might convey the impression that it is a biography by the former head of intelligence in South Africa’s liberation movement armed wing uMKhonto we Sizwe (MK) about his comrade-in-arms Jacob Zuma.

However, the subtitle Kasrils and the Zuma enigma reveals that this volume covers relations between the two men whose paths crossed continuously in MK, the Communist Party (SACP), the ANC and in high government office, dealing with their different assessments of developments.

It opens with a vignette of Zuma and Kasrils, aka Baba and Homeboy, on a two-man mission into Swaziland from Mozambique 35 years ago when Homeboy is injured falling awkwardly from a border fence and, leaning heavily on his comrade, is assisted back over the fence and across country to a safe house.

He recalls Baba talking in hushed tones to his woman friend in the house and hearing the words “umlungu” and “mampara,” adding up to “stupid white man” in the Zulu tongue in which Homeboy was not yet proficient.

Baba’s subsequent return to his comrade with soothing words and a hot coffee is cited to extrapolate an assessment of Zuma as an unkind and two-faced Judas and this is possibly the least convincing episode of the book. Kasrils has examples enough to show Zuma in this light without what might appear a manifestation of recovered memory, although he recounted this tale to various comrades in the 1980s, some of whom deemed it relevant in giving insight into Zuma’s duplicity when it was expressed later.

He encapsulates the core of his argument — the ability of Zuma to subvert through lies and subterfuge the revolutionary movement, including the SACP, while plundering it and undermining its values and role — by recalling an SACP politburo meeting in the Johannesburg party HQ in July 2005.

This was shortly after then president Thabo Mbeki had sacked his deputy Zuma in response to a High Court judgement that he had benefited financially from his adviser Schabir Shaik’s corrupt dealings over a deal with French arms company Thomson-CSF.

Kasrils, Mbeki’s intelligence minister, delivered his assessment of Zuma, highlighting his “tribalism, the question of morality, the fact that he is no working-class hero and the issue of conspiracy and security.”

There was also the issue of corruption although, as he was reminded by party chairman Gwede Mantashe, general secretary Blade Nzimande and deputy GS Jeremy Cronin, big business and the apartheid system were the masters of this field.

Kasrils’s interventions were heard. But he was clearly fighting an uphill battle in light of his comrades’ growing discontent with Mbeki’s government and its sidelining of the SACP and the Cosatu trade union federation, especially over its ditching of the Reconstruction and Development Programme and adoption of neoliberal policies. Nzimande told him that, in most comrades’ view, a Zuma presidency represented “the best opening for the left in this country.”

“You think you can manage him, comrade Blade?” Kasrils responded. “You will discover he is a law unto himself. Mark my words, the party one day will deeply regret this support for Jacob Zuma.”

The story comes full circle with Nzimande’s speech to the 2017 SACP congress almost exactly 12 years later, when the party leader declared that a “marriage of convenience” had lain behind the efforts to replace Mbeki with Zuma adding: “Our trust has been broken and we have been betrayed.”

Kasrils relates in convincing detail the fate of others whose trust was broken and who were betrayed by Zuma, not least Fezekile “Fezeka” Ntsukela Kuzwayo, the HIV-positive lesbian daughter of MK comrade Judson Kuzwayo who had grown up giving both Baba and Homeboy the honorific “Uncle.” Her phone call to Kasrils in November 2005 was direct. “Uncle Ronnie, Jacob Zuma has raped me.”

Fezeka’s brave decision to press charges brought down on her head concerted pressure to change her mind and an avalanche of coordinated abuse, especially from the ANC youth and women’s leagues outside the court, which eventually acquitted Zuma.

However the trial evidence and cross-examination carried extensively in the media, including his bizarre testimony to taking a shower to minimise the risk of Aids, contributed to growing popular disenchantment with Zuma, bringing huge electoral losses for the ANC.

Kasrils tackles the scandals and controversies associated with the Zuma presidency, including corporate state capture by the wealthy Gupta family, diversion of public funds to build his private rural compound at Nkandla, the police massacre of miners at Marikana, high-level though incompetent falsification of emails, politicisation of security units and much more.

He points the finger but tries to understand how and why it was possible for a Zuma to come to the fore and to besmirch the name of a liberation movement that had been all but universally viewed as a model of decency with a leader in Nelson Mandela embodying all the most positive human attributes.

Kasrils returns to the negotiated end to apartheid and introduction of democracy a quarter-century ago, founded on what he calls a Faustian pact when the ANC bought into imperialism’s neoliberal global formula and market fundamentalism, putting the revolutionary change necessary to meet the needs of South Africa’s disenfranchised masses on the back burner.

Patience was preached to the working class and landless peasants, while those with connections jumped on the black economic empowerment gravy train as capitalism’s junior partners.

What is most noteworthy is Kasrils’s lack of bitterness and, indeed, his refusal to subside into cynicism and despair. His Marxism is undimmed and he remains confident that real revolutionary change will come. “Once mobilised and inspired the masses who are the true creators of history have the creativity and strength to storm the heavens,” he asserts in recognisable imagery.

“Call this People’s Power; give it the name of democratic socialism if you will. Another world is possible.”

John Haylett is political editor of the Morning Star