This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

THIS YEAR, Labour took control of the council in the London boroughs of Wandsworth and Westminster. Nearly five decades of Tory control has made these places almost unaffordable for working people on a normal wage.

People today know the Wandsworth Tory council leader from these early times — Christopher “Chopper” Chope — as the “Jurassic era” MP who, more recently, blocked the passage of a private member’s Bill that would have made upskirting a specific offence.

But Chope had another vision — of a gentrified area denuded of Labour voters and the working class in general by a social-cleansing process built around the privatisation of the housing stock.

The old metropolitan borough of Battersea was a long-time centre of working-class political activity. In the early part of the 20th century it had a solid working-class majority on the council, with socialists and Irish republicans setting the pace.

This complex politics of the period is reflected in the street names of the pioneering municipal housing. Freedom Street and Reform Street exist alongside roads with names that evoke the memories of colonial wars — Afghan and Kabul — where crushing defeats were visited, not for the last time, on the imperial invader.

Radical Battersea elected the country’s first black council leader, John Archer. The working man John Burns was elected to Parliament and soon enough turned into a right-wing member of the Liberal Party — only to be eventually followed, as Labour MP for Battersea, by the Communist Party politician Shapurji Saklatvala.

Battersea was a centre of radical — even revolutionary — politics in the interwar years with a strong industrial base and lively local polemicists.

Saklatvala was given to rousing Friday speeches from the balcony of the town hall (now the Battersea Arts Centre) reporting to his constituents on events in the Commons. On one occasion, his famously fiery oratory goaded the police into dispersing his aroused audience with mounted police charges.

Comrade West, who lived in our block of flats, was married to a leading activist in the Battersea National Union of Railwaymen (NUR). When the right-wing leader of the NUR, Jimmy Thomas, spoke at the town hall on the outcome of the 1926 General Strike, the betrayal of which he was complicit, she leapt upon the platform to fetch him a right-hander. Fifty years later she remained an inspiration, sending off our local anti-racism march with a clenched fist and cheers from the window of her flat.

This network of council flats, which passengers passing through Clapham Junction see to the river side of the tracks were, in the words of Chope himself, “a nest of Labour voters.”

The Tories’ chosen instrument for winning political control was social cleansing, carried though most thoroughly in the London boroughs of Westminster and Wandsworth.

Labour leadership of the London County Council (LCC) — it won control in 1934 — was the precondition for a big expansion of public housing. South London lad Herbert Morrison became leader of the LCC and oversaw a big expansion of public housing.

Morrison, whose youthful politics leaned to the left, was serially unsuccessful as a contender for the leadership of the Labour Party and became a wartime Cabinet minister, but when he concentrated on local government, was able to exercise decisive powers over a large area of services.

An old-style social democrat, albeit a right-winger, he oversaw the creation of an integrated public transport system and a big increase in public housing, with the LCC locating big estates in outer London boroughs.

His re-election to Parliament in 1935 put him back in the nexus of power in Labour politics and with the postwar majority Labour government, he was able to give effect to a strategic vision that included the green belt and sponsorship of a new kind of social architecture.

There is a longer discussion to be held about Morrison’s politics and about the nature of the postwar social contract, shot through as it was by imperialist war, colonial repression and welfare state policies.

This was a man who banned the Daily Worker when he was wartime home secretary. As foreign secretary he sponsored the coup that overthrew Mohammad Mossadeq to make Iran safe for the Anglo Iranian Oil Company aka BP. His politics encompassed both an incipient racism and zionism.

But for Morrison, it was all about power to be used in a way that, if deployed today by the right-wing opportunists who infest many London councils, would make even them prime targets for a Starmer-style purge — which in today’s Labour would likely be masterminded by his grandson Peter Mandelson.

The Tories saw the vast expansion of public housing as a threat and they justified their late 20th-century privatisation binge as a response to the notion — attributed to Morrison — that Labour intended to “build the Tories out of London.”

Whether Morrison actually uttered these words is a matter of controversy but it certainly animates the Tories then and now. I first heard it in the 1970s when Chope appeared on my Battersea council estate to defend the Tory administration’s privatisation policies.

It popped up again at the 2019 election count which saw Rishi Sunak loyalist Helen Whately defend her 26,000 majority. A Tory responded to my suggestion that rather than allow the construction of expensive “executive” houses in Kent, our council should build affordable public housing — with the lame response that this would be a 21st-century reiteration of Morrison’s strategy.

In doing so the Tory made explicit, no less than Morrison, that housing is a class question.

If only Labour had, in the intervening years, remained as enthusiastically in support of mass, publicly owned housing at affordable rents we might today have less of a housing crisis.

Today we see the combined effects of decades of bipartisan market-driven housing policies. A system of directly managed council housing has been dissolved by individual right-to-buy policies where much of this formerly publicly owned housing stock in now concentrated in the hands of private landlord corporations.

A proliferation of social housing agencies has fragmented social housing management with the inevitable inefficiencies and corruptions that emerge when public services are detached from democratic control.

Social housing is now mostly managed by private registered providers (PRPs). In Wandsworth there are around 40 of these and between them they own over 9,000 homes in the borough.

The 20th-century Tory technique was to allow the properties to deteriorate, decant the tenants and then rehouse them elsewhere before refurbishing the properties for sale.

This is what happened in the early years of Tory control in Wandsworth to the Vicarage Crescent legacy estate on Battersea’s riverside.

Living conditions were appalling due to overcrowding, damp and mould, while years of neglect made the tenants desperate for improvement. A combination of inspired tenant leadership backed up by the Battersea Law Centre saw the council forced to act only to transform the run-down buildings into a renovated and gated residence for those who could afford London’s rocketing house prices.

Surf the internet today for properties in Vicarage Crescent SW11 and you will see a beautifully tended flower-filled gated courtyard where once rubbish was left uncollected. Here a two-bedroom flat will set you back £580,000. A joint income of over £80,000 is needed to get a property toehold for a small family in this bit of SW11.

There are 2,403 homeless households in Wandsworth and over 6,000 in the housing queue.

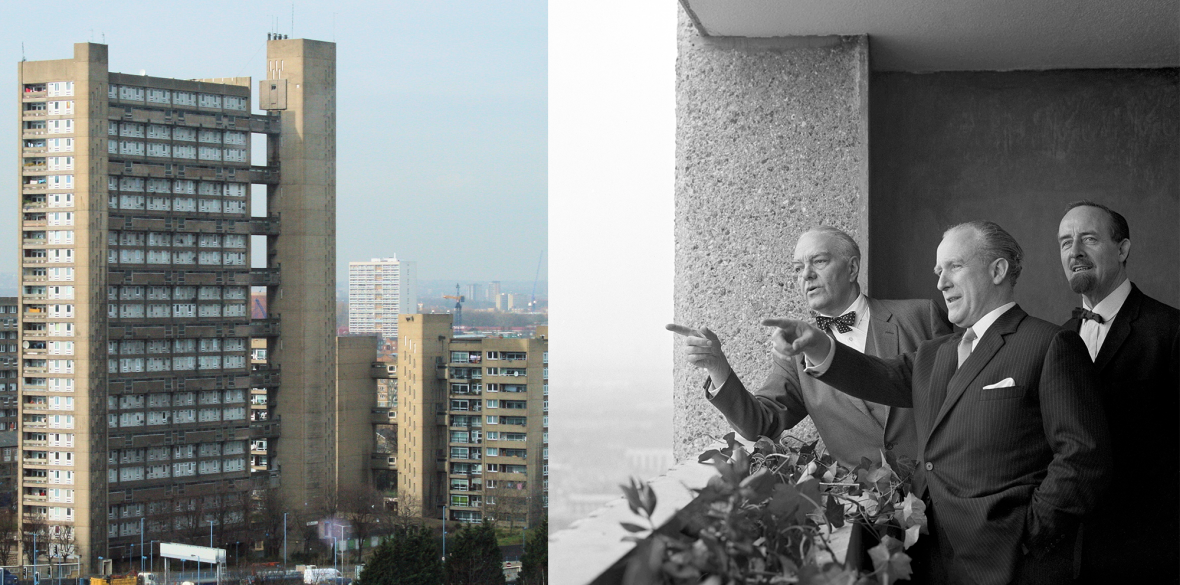

I was struck by the parallels between this process in Battersea and how the renovation of the emigre architect Erno Goldfinger’s enervating modernist housing has been handled.

The bourgeoisification of working-class London is exemplified by the latest stages in the life of his two signature buildings, Trellick Tower in west London and Balfron Tower in the east. In both cases flats in these iconic buildings are up for sale at prices no person in a typical working-class job can afford.

Goldfinger designed the postwar Daily Worker building and the renovation of the Communist Party’s Covent Garden offices as well as schools, the DHSS offices at Alexander Fleming House and several iconic modernist houses.

Today a one-bedroom flat in Balfron Tower overlooking Canary Wharf, much of working-class London and the river, will set you back £365,000. At today’s rates a couple would need a joint income of well over £50,000 to be in with a prayer.

Modernist architecture gets a mixed reception and tower block living is not for everyone. Families with children often prefer living at ground level and the most desirable housing mix would allow for families to be able to stay local and move from one kind of property to another as family circumstances change. The aggregate effect of the capitalist conduct of housing policy — privatisation and a lack of new construction — over the past four decades has been to make this a near impossibility.

Much of modernist housing construction was predicated on a social democratic vision of postwar living which was conceived around full employment, a welfare state that was supposed to take the anxiety and stress out of housing provision, social care, health and education.

We can see how much of this has been dissipated where more or less full employment has been replaced by an even more highly stratified labour market, with many people on the minimum wage, part time earnings, insecure contracts and with the fabric of modern life and public services saturated with market-based measures.

Today’s housing problem can only be solved by a national programme of publicly owned construction with the management of housing devolved to local authorities in a system which give tenants a real voice in a system of democratic control.

Meeting human needs means driving the market out of housing and is no less a necessity than driving it out of the NHS, transport, energy, water, education and social care.

Where postwar social democracy was driven by a sense that public initiative could tackle many of society’s problems, Labour’s leadership today has a miserable vision for Britain that would leave the market in command.

Nick Wright blogs at www.21centurymanifesto.wordpress.com.