This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

THE letters page of the Morning Star features an interesting exchange between proponents of a proportional representation (PR) system for elections and those who favour continuing with Britain’s first-past-the-post (FPTP) system.

A politically respectable argument for FPTP is that it provides the best chance for a majority Labour government.

Its supporters argue that PR leads to coalition government with the progressive tendency always at the mercy of its least progressive component.

FPTP itself produces bizarre outcomes. The Scottish National Party in 2019 won 3 per cent of the votes but 59 seats which is more than 9 per cent.

The Tories got 43.6 per cent of the vote (against their 42.4 per cent in 2017) but won 48 extra seats.

The Greens got 1.6 per cent and one MP but under a pure PR system might have got four or more if their sympathising voters who — under FPTP vote for their second preference — would be more likely to vote for them.

The arguments for PR are grounded in the undeniable truth that the more proportional it is, the more representative it is.

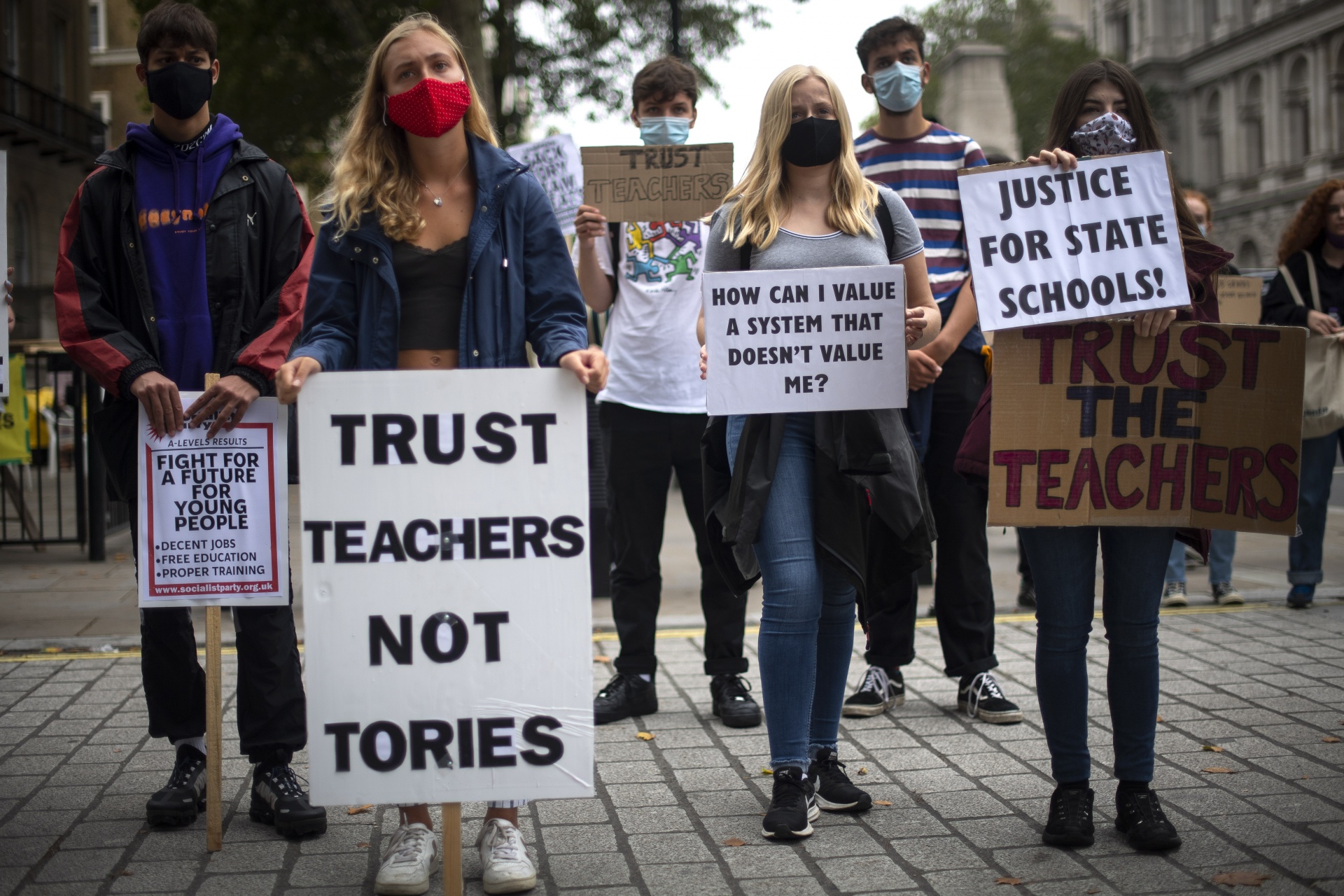

Controversy in labour movement circles was highlighted most recently by changes to the system of electing constituency representatives to the party’s national executive committee imposed by the new leadership.

FPTP had previously meant that a broad left-wing majority was able to deny the right wing any seats to this category of NEC membership. The new system was adopted, presumably because it would allow at least some of the right wing to get elected.

Criticism of the decision to introduce the single transferable vote (STV) system of PR centred not on the deficiencies, real or imagined, of the new system but on the arbitrary nature of the decision to introduce it without seeking endorsement by a conference vote.

Only a complete naif would believe that this controversy is exclusively about the principles involved and is divorced from the probable consequences of either system.

There are several varieties of proportional voting and which is favoured usually depends on the likely outcome.

In parliamentary elections the STV system necessitates multiple-member electoral districts, with voters listing individual candidates or parties in order of preference.

During the count, as candidates are elected (by reaching the quota) or eliminated (by coming last in each round), the surviving candidates stand a better chance of making it to the finish the more they can attract a critical range of support.

The Irish are perhaps the most sophisticated electorate in the world and both voters and party activists are adept at calculating the probable consequences of any preferential voting strategy.

Oddly, Sinn Fein cocked up rather badly in the last Dail election by failing to nominate enough candidates in enough multimember constituencies and thus was unable to harvest what turned out to be an unprecedentedly large body of support both direct and transferred.

Some STV systems facilitate voters electing candidates across party lines, or allow them to choose among a party’s candidates and or vote for independents.

Because they know their votes are not wasted, electorates quickly learn the subtleties of PR and tailor their preferences in the knowledge that even if their priority candidates are not elected, they still have some influence on the result.

Some PR systems dilute their representative character by setting minimum thresholds. Turkey, for example, has a high threshold to reduce the impact of Kurdish and opposition parties, but in recent elections these forces have united to overcome the barrier.

In Germany both the free-market liberal FDP, the right-wing AfD and Die Linke (The Left) worry about falling below the 5 per cent threshold.

Our ruling class is extremely relaxed about the high levels of abstention in British elections and increasingly favours voter suppression techniques borrowed from the US. The vast bulk of abstainers are working class, including many who have been deeply alienated from politics.

Some abstentionism arises from the sense that in constituencies that are either overwhelming Labour- or Tory-supporting (working class or middle class) the vote makes little difference.

In a carefully constructed statement, Labour leader Sir Keir Starmer said: “We’ve got to address the fact that millions of people vote in safe seats and they feel their voice doesn’t count. That’s got to be addressed by electoral reform. We will never get full participation in our electoral system until we do that at every level.

“I would consult the party membership on electoral reform and include it within the constitutional convention that looks at wider democratic renewal — including abolishing the Lords and furthering devolution on the principles of federalism.”

The recovery of the three million-plus voters lost by New Labour — partially by Ed Miliband and more dramatically by Jeremy Corbyn in 2017 — were the most distinctive and encouraging features of recent years.

But Boris Johnson’s coup de theatre in capturing alienated Labour voters — and the Tories’ earlier effective tactic in capturing and then cannibalising the Liberal Democrats — shows how voters can be detached from their traditional class and political loyalties can be won or neutralised, and how these changes can produce unrepresentative results.

The more reflective sections of the political elite understand how the Brexit referendum — because every vote counted — allowed people who usually saw little point in voting were mobilised to turn out.

It gave a sense that a mobilised working class — in a country like Britain where the class divisions are sharpening — is a very powerful force.

Labour’s right has, in recent decades, worked on the assumption that working-class and left-wing voters have nowhere else to go.

With the breakdown of this very temporary truth and with Corbyn’s election as party leader, Labour’s rightwingers completely lost their bearings and a big part of them worked for or consciously risked electoral damage by their repeated attempts to unseat Corbyn.

It is pointless to speculate that if Corbyn and his team had fought for mandatory reselection of candidates, had dealt more convincingly with the Parliamentary Labour Party and the allegations of anti-semitism that they might have made a bigger advance in 2017 or mitigated the losses in 2019.

The present balance of forces in Labour is what it is and the institutional and parliamentary power of the Labour right is still very considerable.

Starmer’s election showed that while a big proportion Labour members favour left-wing policies — and while he was compelled to offer verbal support for them in order to get elected — they still see Parliament as the place where politics gets done.

Proportional voting of various kinds has been introduced in Scotland, Wales and London; a version was used in recent elections to the EU Parliament, while the British statelet in Northern Ireland uses a form of PR.

People are getting used to it and while Britain has a fragmented system of local government with some areas opting for directly elected mayors with extensive powers, this is always in a context of reduced resources.

Both Starmer and his deputy Angela Rayner have come out strongly in favour of replacing the House of Lords and this is not the only vestige of feudal power and privilege that should be done away with.

There is a lively discussion about a new constitutional framework — maybe with a proportionally elected second chamber — for governing the relations between the constituent nations of Britain, and this is seen by some who oppose Scottish or Welsh separation as a basis for a federal state.

It is hard to see any principled objection to the introduction of PR in local elections. It may stimulate a higher turnout, draw more people into activity and give voice to a wider range of people. It would certainly make local politics more lively.

What does this mean for more fundamental change?

Whenever Labour has achieved elected office, its efforts to improve conditions for the majority of our people have been tolerated only as far as such reforms could be accommodated within the existing framework.

Whenever the basic foundations of ruling-class power and wealth have been threatened, Labour’s right wing, principally in Parliament, has worked against the party.

After the fall of the first minority Labour government under party leader Ramsay MacDonald in 1924, the Tories and the Secret Intelligence Service (MI6) circulated a letter forged as coming from the Communist International and purporting to detail Communist Party support for Labour.

Although the Tories won the subsequent election, Labour support actually rose by a million votes.

Later, in 1931, under the second minority Labour government, the Labour right went into coalition with the Liberals and Tories to form the Conservative-dominated, reactionary Depression-era national government.

In 1951, the FPTP system caused the fall of the Attlee-led Labour government. Labour’s vote had actually increased (to 13.9 million, compared with 13.2 million in the 1950 general election and 11.9 million in 1945) and it won 230,000 more votes than the Tories. However, the Conservatives ended up with a Commons majority of 17.

That FPTP makes Labour vulnerable was demonstrated when, in 1981, a section of party’s right wing broke away to form the short-lived Social Democratic Party (SDP), which, in alliance with the Liberals, ensured Margaret Thatcher’s 1983 election victory.

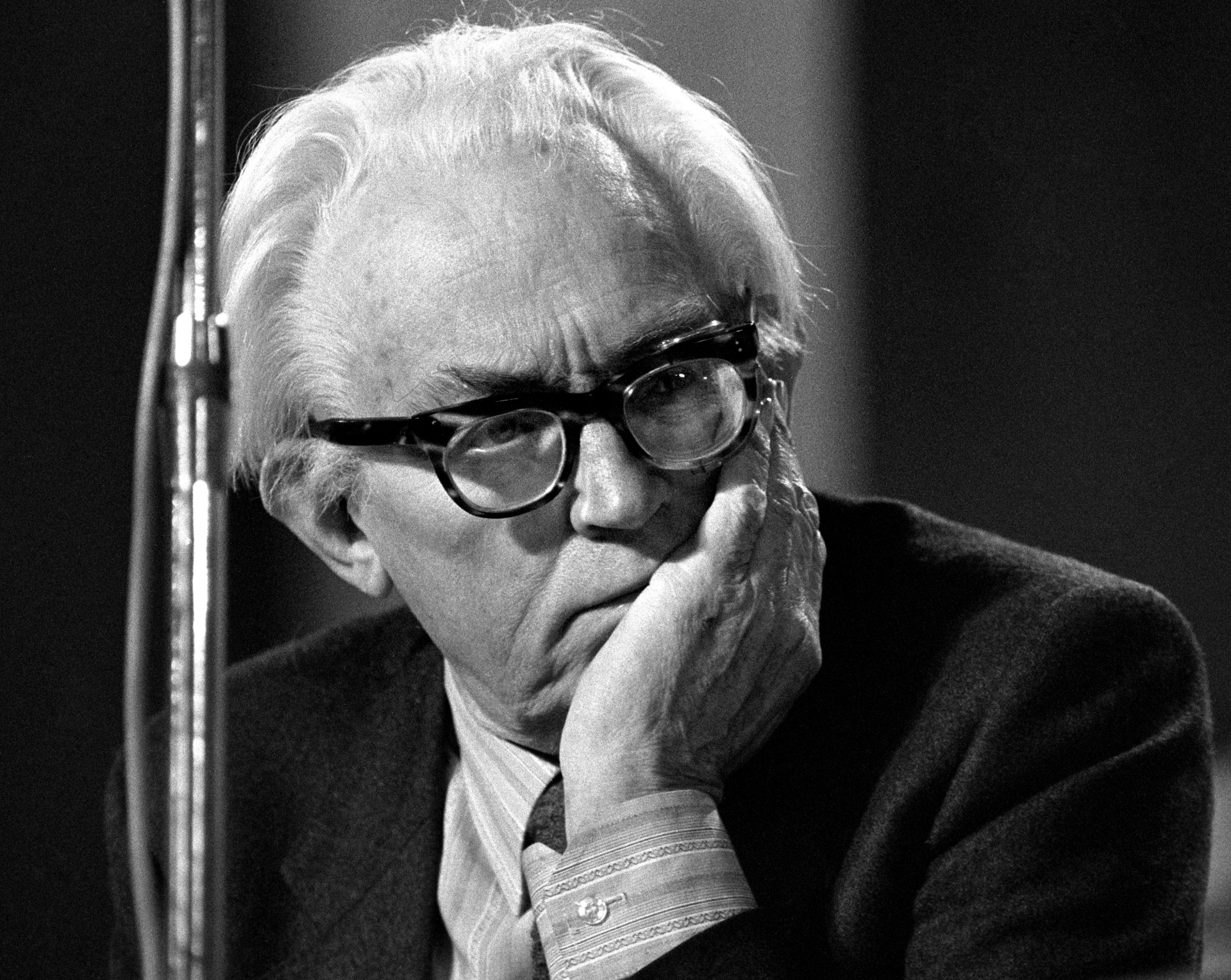

Labour, under left-wing leader Michael Foot, had led in the opinion polls throughout most of 1981, despite the formation of the SDP in March that year, winning a succession of by-elections and only slumped with the outbreak of the Falklands conflict.

The lessons of history are that Labour has a chance of forming a radically reforming government only when the working class and its allies are mobilised and united and when the mass popular mood acts as a brake on the tendency of the right to side with the class enemy.

Labour itself is a coalition of contending class forces and every Labour government has been a “coalition government.”

Experience shows that the inner-party battle for policies is an unproductive exercise unless Labour is led by and represented in Parliament by people committed to a transformative manifesto.

The question, then, is whether it is possible to transform a Labour election victory into an opening towards working-class political power, with a state transformed to carry through a socialist transformation. A key section of our ruling class understands this as a real risk.

We have seen in the last few years how Britain’s ruling class set about two vital tasks necessary to contain a serious threat to its power and wealth. First, it reconstituted its preferred party of power to appeal to a section of the working class that Labour had alienated over a slogan that allowed Johnson to present himself as the instrument of a democratic mandate over an elite intent on thwarting the referendum result.

The second task, again completed with the active participation of the Labour right and the support of the middle ground — and even an eccentric fringe of ultralefts — was to present Labour as the party to get Brexit undone.

Every prop of the present system was mobilised, the media and the judiciary, the intelligence and defence Establishment, the Nato and EU apparatus, foreign powers, including the US and Israel, a majority in the Parliamentary Labour Party and a section of the party apparatus to render Labour incapable of winning an election — and the Tories capable again of winning.

So far the ruling class has been playing to win — and the labour movement to lose with dignity.

Nick Wright blogs at 21centurymanifesto.wordpress.com.