This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

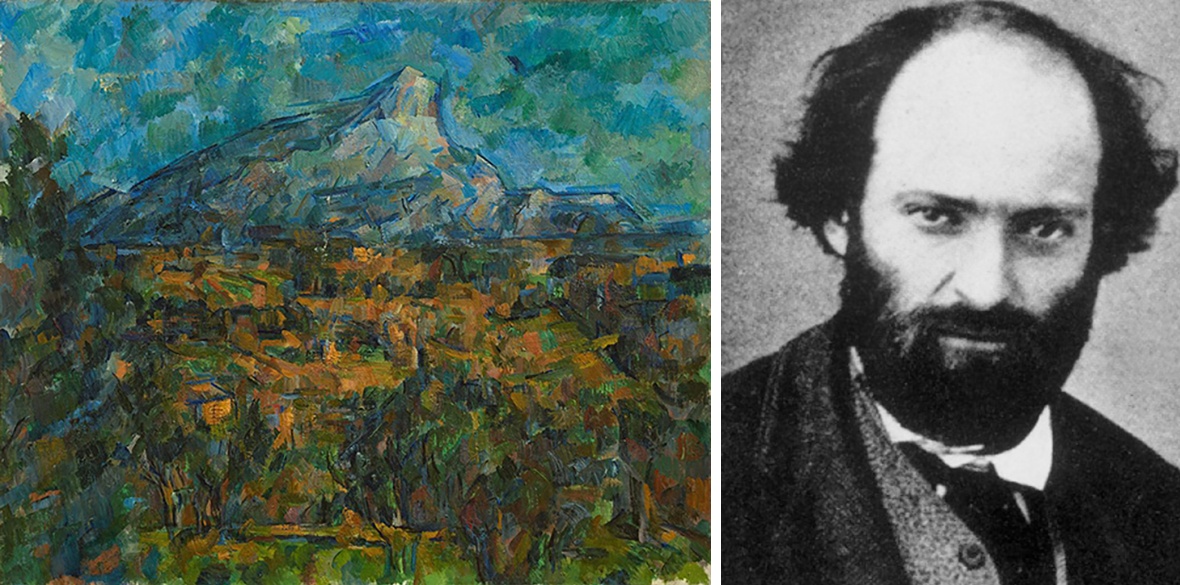

FOR 18 years, between 1888 and 1906, Paul Cezanne kept returning to the Mont Sainte-Victoire, fascinated by the rugged, bare rock face of this 1,011-metre-tall mountain near his home town of Aix-en-Provence at the foot the southernmost tip of the Alps.

He may not have climbed it once, but in its shadow he did relentlessly reach for a different peak — an ultimate rendition of an infinitely complex visual experience.

“Look at Sainte-Victoire there. How it soars, how imperiously it thirsts for the sun,” he once commented. “For a long time I was quite unable to paint Sainte-Victoire; I had no idea [how] to go about it.”

This remarkable quest is at the heart of all modern painting and Cezanne is rightfully considered to be the precursor of the transformative liberation of form that ensued.

Pablo Picasso referred to him as “the father of us all,” adding that he was “my one and only master.”

No idle words these. But Picasso wasn’t alone — Edgar Degas, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Paul Gauguin, Kasimir Malevich, Georges Rouault, Paul Klee and Henri Matisse all concurred.

In turn Cezanne’s methodical approach to painting was initially shaped by the perpetual anarchist rebel Camille Pissarro — his mentor and lifelong friend.

They shared a passion for a cerebral, conscious pursuit of intellectual solutions to problems of representation.

“Painting is damned difficult — you always think you’ve got it, but you haven’t,” Cezanne would observe.

He was fascinated, like most people at the time, with stereoscopes — binocular-like devices that presented each eye with a slightly altered image of the same, which then combine in the brain to give the perception of depth.

He also knew well the theory of 18th-century Anglican bishop George Berkeley who posited that the third dimension — depth — cannot be directly perceived by the eyes because the retinal image is two-dimensional, as in a painting.

Berkeley argued that to have visual experiences of depth is not inborn but could come as logical deduction from empirical learning via other senses such as touch.

For Cezanne the task was to combine “the eye and the mind,” and ensure “each of them aided the other.”

The visual progression of such symbiosis is manifest in the latter Mont Sainte-Victoire scapes, where he accomplishes that radically new attribute of simultaneously exhibiting spacial depth and flat design. You cannot abstract the brushstrokes from the shapes they represent or vice versa.

“The landscape,” Cezanne once intimated, “becomes human, becomes a thinking, living being within me.

“I become one with my picture … we merge in an iridescent chaos,” adding elsewhere: “Landscape is reflected, humanised, rationalised within me.

“I objectivise it, project it, fix it on my canvas.”

In 1912 Albert Gleizes and Jean Metzinger published the first major treatise on Cubism, Du Cubisme, where they pay lavish tribute to Cezanne: “[He] is one of the greatest of those who changed the course of art history … From him we have learned that to alter the colouring of an object is to alter its structure.”

Ernest Hemingway compared his writing to Cezanne’s landscapes: “[I] was learning something from the painting of Cezanne that made writing simple true sentences far from enough to make the stories have the dimensions that I was trying to put in them.”

Cezanne, debilitated by diabetes, died aged 67 on October 22 1906 of pneumonia following a severe chill caught while working in the fields.

He was buried Saint-Pierre cemetery in his hometown of Aix-en-Provence. His legacy is with us to this very day.