This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

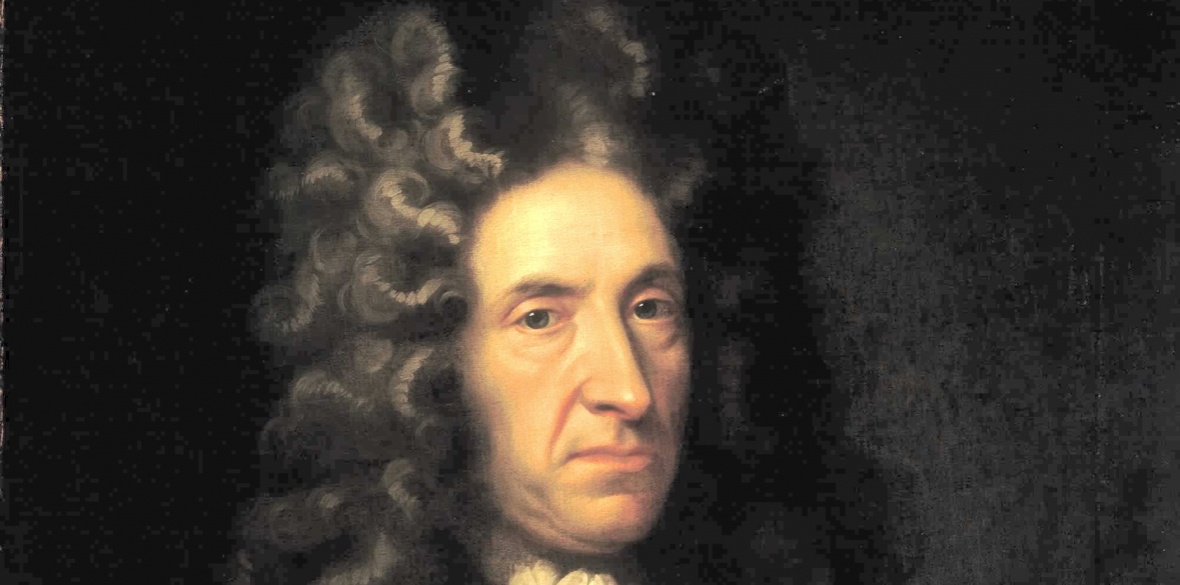

KNOWN to millions, even those who have never read Daniel Defoe’s popular desert-island story, Robinson Crusoe has never failed to engage the interests of not only enthusiasts for tales of adventure but also literary critics, sociologists, economists and psychologists.

Widely recognised as the first modern novel, Defoe’s work has been claimed as “a core mythic text of Western and capitalist civilisation over the last three centuries,” with Marx criticising classical bourgeois economists who seized upon the enterprising marooned Crusoe, reduced to the state of natural man, as a model for a perfect market economy.

They had not noticed that he had nevertheless imported to his island, along with the useful tools retrieved from his shipwreck, the ethos of the burgeoning capitalist society in the outside world. Crusoe even kept daily accounts of profit and loss.

James Dunkerley’s book initially provides a fairly full synopsis of the original narrative, which covers much more of Crusoe’s life than his island sojourn and includes his philosophical observations on his experiences.

It’s followed by “the Robinsonade,” which ranges over the early enthusiastic critics such as Rousseau and Coleridge – who described it as a work “worthy of Shakespeare” – through the succeeding 20th-century academic thickets of academia. As the author warns: “Here come the French intellectuals. Please take a deep breath.”

Understandably, this section also deals with more modern descriptions of interesting adaptations questioning the significant absence of any sexuality in poor Robinson’s life which, according to James Joyce, was one of “sexual apathy.”

In conclusion, Dunkerley delivers an informative contextual account of the author of this fictional autobiography. The “hyperactive” Defoe turned his prodigious energies to mercantile trade as wine merchant, brickyard owner, journalist, novelist and as both government critic and spy-provocateur. For his Whig masters he was “a radical star.”

In appraising what is unquestionably Defoe’s finest poem, his Satyr on The True-Born Englishman, where, after describing the mixture of races that fuel our “native” bloodline, he concludes: “From this Amphibious, ill-born mob began/That vain ill-natured thing, an Englishman,” Dunkerley believes he mirrors not only his own times but “the age of UKIP, the DUP and Brexit.”

Published by O/R Books, £12.